As I’ve mentioned before, 19th-century Roman Catholic burial records did not generally record a cause of death for the deceased, but there were exceptions to this general rule. In cases where a death was considered unusually tragic, dramatic, or violent, the priest might note the cause of death in the parish register.

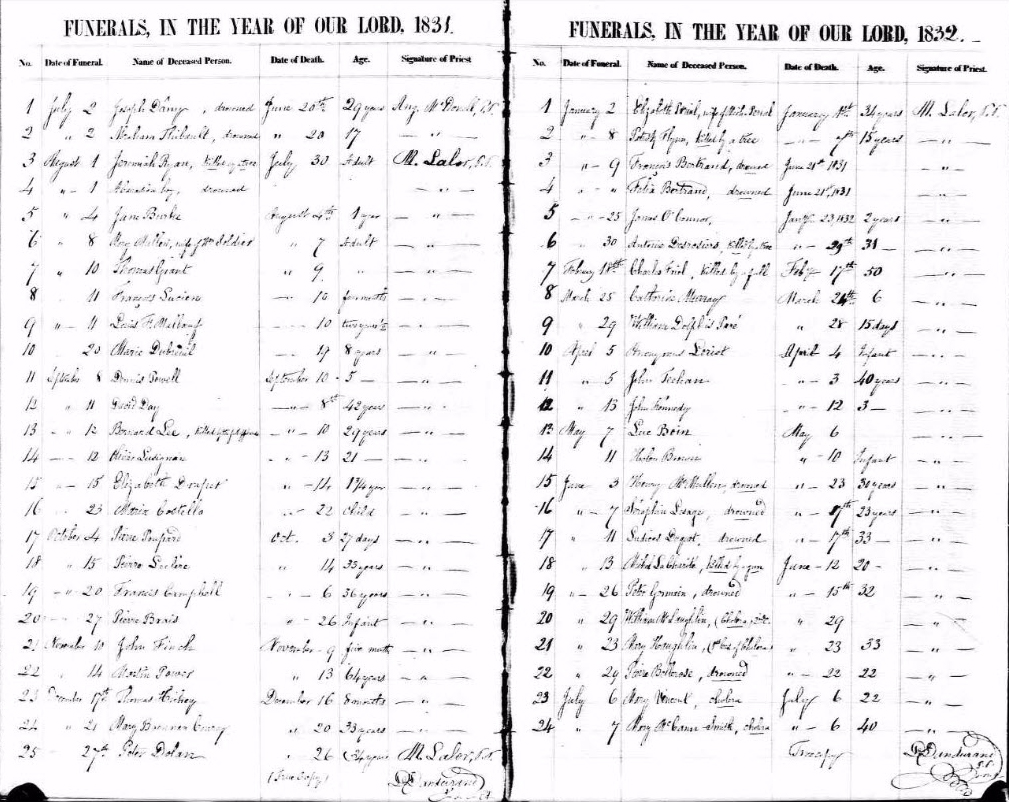

Here’s an interesting example of some exceptions to the rule, which speak to the very real hazards of early settler life in Upper Canada (more specifically, in the Bytown [Ottawa] area). These two pages of burials for the years 1831 and 1832 are from the index of baptisms, marriages and burials for the parish register of Notre Dame Basilica, Ottawa.1 (More on this index in an upcoming entry on search tips for this register).

On the page which lists burials from 2 July to 27 December 1831, most listings do not have a notation of the cause of death, which was in keeping with standard practice. On the page which lists burials from 2 January to 7 July 1832, on the other hand, 15 of the 24 listings do have a cause-of-death notation, which was a bit unusual.2

The causes of death recorded in these two pages offer a rare glimpse into the living conditions of a frontier environment that was fraught with perils and pitfalls. Death by drowning, for example, was an occupational hazard for lumbermen; and there were also some drowning fatalities experienced by labourers working on the construction of the Rideau Canal. And in performing the settlement duties of clearing and cultivating one’s acreage (a requirement for gaining a grant to Crown land), a man might be killed by the fall of a tree (“killed by a tree” is noted for several men on the above two pages).

And if the water or the woods didn’t kill you, if you were in Bytown in 1832, there was a very real chance that you might be carried off by cholera.

In the spring and summer of 1832, a cholera epidemic swept through Bytown, which “prompted the creation of the first Board of Health for Bytown” and which “also increased existing hostility towards immigrants, who were largely blamed for the outbreak of the disease” (“Cholera Wharf,” Heritage Passages: Bytown and the Rideau Canal [http://www.passageshistoriques-heritagepassages.ca/ang-eng]). In the image above (burial listings from 3 June 1832 to 7 July 1832), there are four cholera deaths recorded, for one adult male and three adult females. And in the three pages that follow (burials from 7 July 1832 to 19 November 1832), there are 37 cholera deaths recorded out of a listing of 58 burials. Men, women, and children alike might succumb to this dreaded disease: when it came to age and sex, cholera was an equal-opportunity scourge (though not when it came to social class: the poor were much likely than the wealthy to be struck by cholera, which was most often transmitted through contaminated drinking water).

“Drowned;” “killed by a tree;” “killed by a gun;” “cholera” (all of which causes of death can be found in the above images): Roughing It in the Bush really was quite rough, evidently.

- Basilique Notre Dame d’Ottawa (Ottawa, Ontario), 1829 (Index), image 1411 of 1836, Funerals, 1831 and Funerals, 1832, database, Ancestry.ca (http://www.ancestry.ca/: accessed 25 April 2015), Ontario, Canada, Catholic Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1747-1967. ↩

- Another unusual, and especially poignant, exception can be found in Notre Dame’s burial listings for July and August 1847, where we find page after page of typhus deaths. ↩